Welcome to Snapshots of Social Science - a monthly newsletter where we bring you recent developments in the diverse fields of social science research. Learn more about us here.

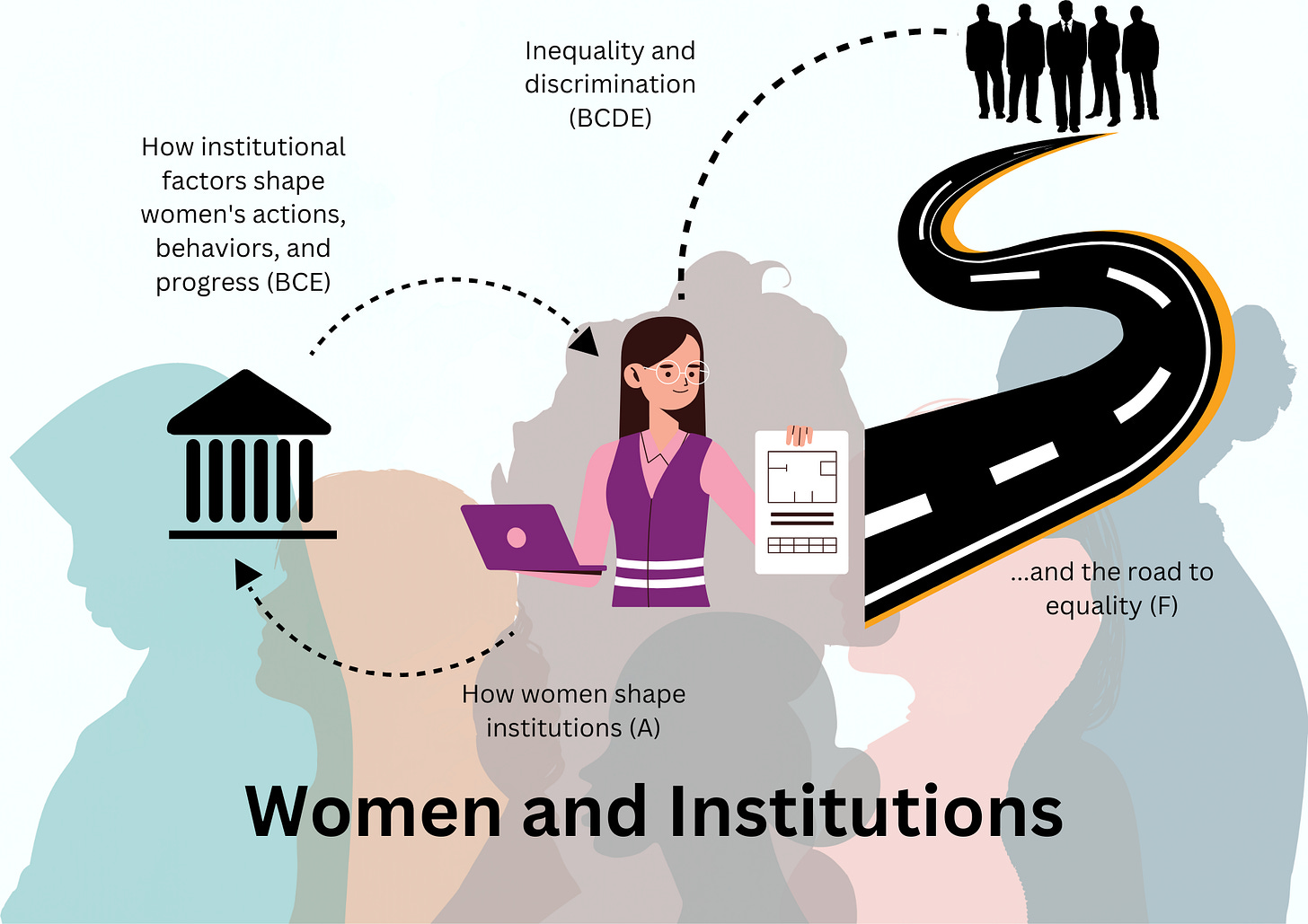

This month, we will look at Women and Institutions. Women play a big role in shaping institutions. Recent research observed that US states with women governors had fewer COVID-related deaths. On the other hand, institutional factors like work environment, structure, and stereotypes impact women’s responses to the challenges they face. And unfortunately, some of these challenges include discrimination, unequal wages, and harassment. The road to gender equality is long, but we are taking small steps in that direction. In this month’s newsletter we will see examples of research that looks at how women shape institutions and vice versa, barriers that women face in institutions, and how to bridge the gender gap. For this, we draw from research in business, psychology, and sociology.

Before we begin, please consider subscribing to ICJS Social Science by clicking the button below! This will ensure that each edition of our newsletter makes its way to you every month. We would truly appreciate it if you spread the word about us as well - our impact grows with each additional reader.

Research Map

News from the field

(A) Female executive leadership and corporate social responsibility (🇺🇸 🇨🇳 🇦🇪 🇨🇦)

Women remain underrepresented in the top management of companies. Parallelly, companies have shown a growing interest in CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility). Past research has shown that increased participation of women in the company leadership has increased CSR activities. But what are the specific ways in which this happens? Researchers have tried to answer this question using data about executive teams in companies before and after the 2008 global financial crisis.

The researchers found that increased participation of women in the executive team is associated with better CSR in those companies. Specifically, this happens in two ways. First, increased participation of women leads to companies paying attention to the concerns of CSR, like the community, product, employees, and the environment, which have a long-lasting negative impact on the company. Second, during times of economic uncertainty (like the financial crisis), increased female participation is associated with decreased investment in newer CSR activities, giving priority to financial stability and ensuring financial commitment to the current CSR activities. Both findings suggest that increased women’s participation in executive teams leads to better CSR in the company

These findings are important because they specify the particular ways in which women in top positions bring value to companies. It is important for companies to increase their gender diversity especially in the top management, given that women face the glass ceiling (see the next article). In the future, researchers can study the perceptions of the public when CSR activities improve with increased female participation.

Research has found that women managers implement more family-friendly policies for their subordinates. 🇯🇵

Read this paper on how the number of women on a bank’s board is associated with how the bank manages its earnings. 🇨🇳 🇬🇧

Researchers have found that companies with a greater number of women in top management face fewer lawsuits. 🇺🇸

(B) Network Recruitment and the Glass Ceiling: Evidence from Two Firms (🇺🇸 🇨🇦)

Social networks are important, especially for getting hired through referrals. If these networks have gender homophily (persons from the same gender being more likely to group together), a predominantly male network can be disadvantageous to women. What is the extent of this disadvantage? And at what job levels does it operate? Researchers try to answer this question using data from two firms.

Data from both the firms suggests that using networks to recruit employees actually leads to increased hiring of female employees. But the effects of this network-recruitment is different at different job levels. As the level of the job increases, network recruitment favors fewer women. That is, in both the firms, researchers see the glass ceiling pattern: women face invisible barriers in navigating to the top of the leadership hierarchy. Because the data-collection was not done entirely by the researchers (both firms provided them with data), they made some reasonable approximations and assumptions where the data was missing.

However, this research is important, both in theory and practice. This work builds on existing literature by suggesting the specific ways in which network recruitment contributes to the glass ceiling. And it also points to the importance of analyzing the data companies collect—in this case, it will help companies use networks in appropriate ways to recruit employees. In the future, researchers could conduct behavioral experiments by giving referrers differential incentives for referring male versus female candidates. The model built here might enable researchers to predict the resulting gender composition of the workforce.

Read this paper to understand the role of social networks in the bamboo ceiling—underrepresentation of Asians in top leadership. 🇺🇸

See this paper to understand the impact of network-based recommendation algorithms on minorities and other social processes. 🇩🇪 🇦🇹

Researchers study how diversity and efficiency, generally thought of as traded off with each other, can in fact work together to enable the spread of information through networks, leading to more inclusion of minority groups. 🇺🇸

(C) Women in Economics: Stalled Progress (🇺🇸)

The proportion of women in the academic discipline of economics has not increased in the past two decades, after a period of rise in the 1970s and 80s. And economics particularly falls behind in terms of gender parity, even compared to fields like STEM which are commonly associated with gender disparity. Are there any specific features of the field of economics that are not conducive to women? Researchers tried to answer this question by synthesizing the findings of multiple studies.

In this paper, researchers first describe the difference in representation of men and women by looking at the proportion of women as PhD students and faculty in different academic fields, and PhD dissertations grouped by topic and gender. Based on this data, the researchers advanced different explanations, including the lack of social network and mentorship for female faculty and the particularly hostile environment of academic economics.

While the researchers acknowledge that some of these barriers to women are difficult to quantify, this research gives us a broad sociological view of how the culture of particular fields, in addition to systemic barriers that women face, impact women differently. In the future, researchers could look at how the perception of outsiders (i.e., academics from fields outside of economics) about economics could impact women’s progress in this field.

This paper describes models of mentorship for women in academic medicine, where they are generally underrepresented in the top positions. 🇺🇸

Read this article for more information on how the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately affected female academics, and what to do about it. 🇺🇸 🇬🇧

This is a report on the state of women in economics done by the Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession (CSWEP) in 2020. 🇺🇸

(D) The confidence gap predicts the gender pay gap among STEM graduates (🇺🇸)

In some STEM fields, average salaries of men and women are not similar. Previous research has pointed to multiple explanations for this, from an unfair burden of domestic responsibilities to employer discrimination. But addressing the particular pay gap between recent college graduates in Computer Science and Engineering fields, researchers have advanced a potential explanation: gender differences in self-efficacy (one’s own confidence to be able to succeed).

Researchers studied over 500 students from multiple universities for a period of three years—from when they were still in college to getting their first job—to track their beliefs about self-efficacy, importance of pay, and importance of workplace culture. Researchers combined this data with data about the subjects’ salaries and found significant influence of self-efficacy. But how would that affect pay? Further analysis indicated that this difference in self-efficacy influences the intent to enter CS and Engineering jobs. So women, having lower self-efficacy ratings in general, were less likely to enter CS and Engineering jobs (which are high paying) in the first place, which could explain the pay gap.

Since this was an observational study, it could not establish that differences in self-efficacy cause the pay gap, but experimental research could do this. This sort of research is important as it studies the interaction between psychological and sociological factors that contribute to the pay gap. One possible future direction to consider can be how differences in self-efficacy can influence individuals’ social networks, and therefore social capital, possibly widening gender disparities.

In this paper, researchers find that the gender pay gap in New Zealand universities was not sufficiently explained by research performance and age differences between different academics. 🇳🇿

In this study, women report more comfort, connection, and confidence after attending an all-women small Computer Science course at a large university. 🇺🇸

Researchers find that women build less effective social networks compared to men, and part of the reason is personal hesitation. 🇩🇪

Researchers in the past believed that women and under-represented minorities (URM) in STEM fields in college typically performed worse than other students because of their individual academic preparation and socioeconomic status. However, more recent research has focused on the role of institutions and stereotypes in explaining performance. In this paper, researchers studied how feelings of belongingness, or fit, could explain differential performance.

Researchers surveyed and interviewed women and minority students from different universities, asking them questions about their feelings of fit, biases they faced, and their social circles they could get resources and advice from (extent of their social capital). They found that students who fit well had characteristics of majority student groups, and those who did not, were subject to differential treatment. But students who had access to advisors and community groups in their social network, who told them to expect this discrimination, were more persistent and stuck through their program.

This finding is important for academic institutions because it indicates that they should put in more effort to increase a collective sense of community, access to social capital, and also focus on culture more than individualized interventions. In the future, researchers could study the implications of perceptions of fit on not just academic performance, but also participation in extracurricular activities like internships.

This paper describes how an academically threatening environment in STEM contributes to underrepresentation of women in these fields. 🇺🇸

Researchers describe how being outnumbered and stereotyped affects the career of women in STEM. 🇳🇱

Read this review article for the studies on women entrepreneurs in STEM fields. 🇮🇹 🇳🇴

(F) Think Funny, Think Female: The Benefits of Humor for Women’s Influence in the Digital Age (🇫🇷 🇺🇸 🇮🇱)

When we think of humor, it is not typically a humorous woman who comes to mind. And previous research shows that women in positions of power were perceived as less competent if they engaged in humor compared to if they didn’t; on the other hand, men who told the same jokes were perceived as more competent than their serious counterparts. Should women stop being funny to be more influential, then? Researchers think not.

Researchers used TED talks to dispel this advice. They analyzed humor in these talks by looking at parameters like humor, i.e., how many times the audience laughed, and influence, i.e., how many views and the types of reactions the talk got. They found, surprisingly, that female speakers who were humorous were more influential, not just compared to other non-humorous female speakers, but also male speakers who were just as humorous as well. So humor not only closed the gender gap, but also was advantageous for women.

In the digital world, this is an important finding. Using humor appropriately can be helpful for women to exert more influence in the digital space. While this is not the only way to reduce gender disparities in the world, important future directions include studying the use of humor in workplace conversations instead of talks or presentations, and the perceptions of managers towards a woman subordinate’s humor.

Read this book chapter to see the take of sociolinguistics on whether gender plays a role in leadership discourse and humor. 🇬🇧 🇲🇾

In this paper, researchers examine the evolutionary explanation to different responses of men and women to different types of humor in advertising. 🇩🇪

Researchers study the perceptions of employees to their manager’s humor and the mediating role of gender. 🇮🇱

Research Community Map

This month’s newsletter featured research from 7 US States, and 6 countries

Spread the Word!

Thank you so much for reading! Please share this newsletter with anyone who would be interested. Press the button below to share!